Michael Cysouw <cysouw@mac.com>

A Pandoc filter for linguistic examples

tl;dr

In the field of linguistics there is an outspoken tradition to format example sentences in research papers in a very specific way. In the field, it is a perennial problem to get such example sentences to look just right. Within Latex, there are numerous packages to deal with this problem (e.g. covington, linguex, gb4e, expex, etc.). Depending on your needs, there is some Latex solution for almost everyone. However, these solutions in Latex are often cumbersome to type, and they are not portable to other formats. Specifically, transfer between latex, html, docx, odt or epub would actually be highly desirable. Such transfer is the hallmark of Pandoc, a tool by John MacFarlane that provides conversion between these (and many more) formats.

Any such conversion between text-formats naturally never works perfectly: every text-format has specific features that are not transferable to other formats. A central goal of Pandoc (at least in my interpretation) is to define a set of shared concepts for text-structure (a ‘common denominator’ if you will, but surely not ‘least’!) that can then be mapped to other formats. In many ways, Pandoc tries (again) to define a set of logical concepts for text structure (‘semantic markup’), which can then be formatted by your favourite typesetter. As long as you stay inside the realm of this ‘common denominator’ (in practice that means Pandoc’s extended version of Markdown/CommonMark), conversion works reasonably well (think 90%-plus).

Building on John Gruber’s Markdown philosophy, there is a strong urge here to learn to restrain oneself while writing, and try to restrict the number of layout-possibilities to a minimum. In this sense, with pandoc-ling I propose a Markdown-structure for linguistic examples that is simple, easy to type, easy to read, and portable through the Pandoc universe by way of an extension mechanism of Pandoc, called a ‘Pandoc Lua Filter’. This extension will not magically allow you to write every linguistic example thinkable, but my guess is that in practice the present proposal covers the majority of situations in linguistic publications (think 90%-plus). As an example (and test case) I have included automatic conversions into various formats in this repository (chech them out in the directory tests to get an idea of the strengths and weaknesses of the current implementation).

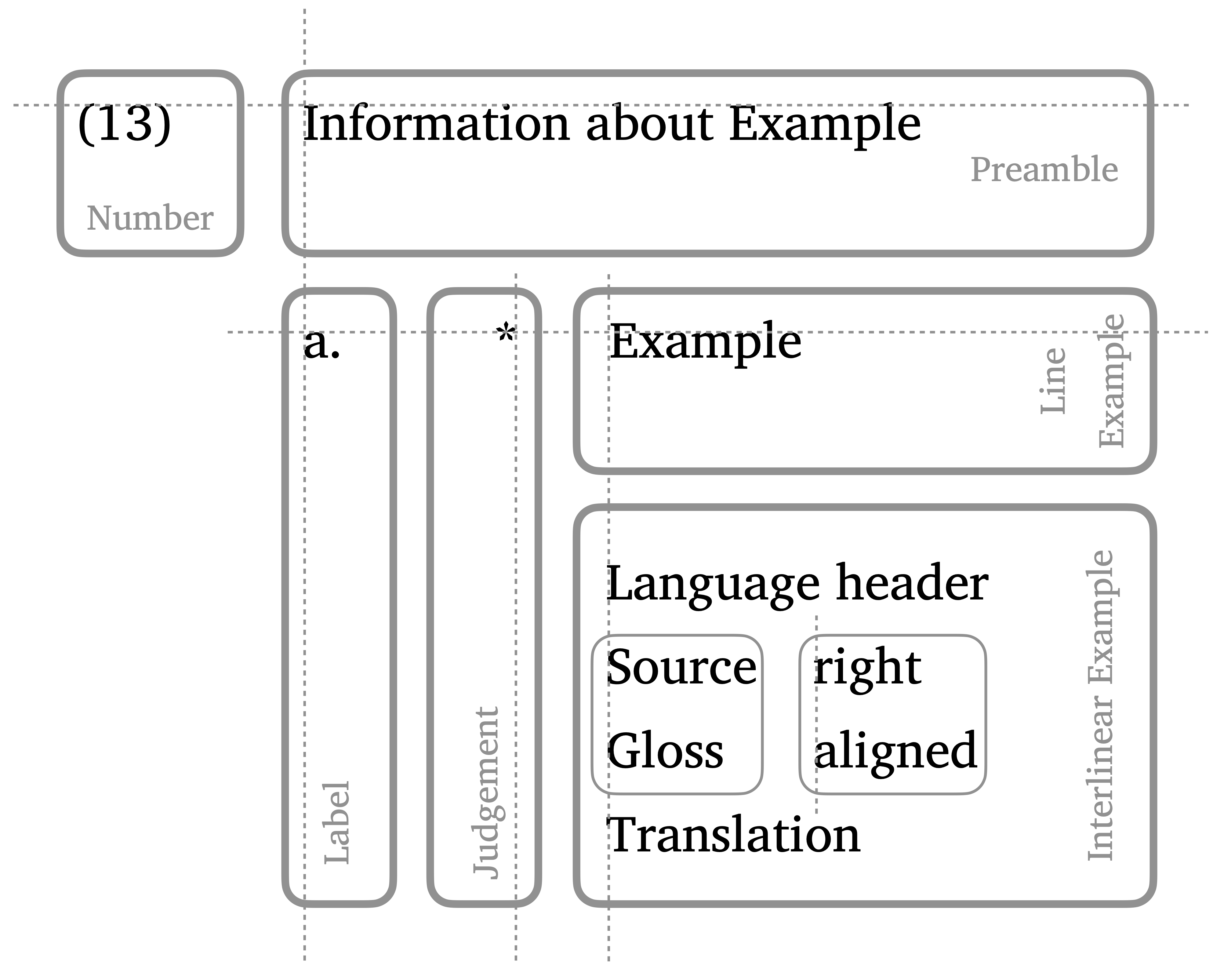

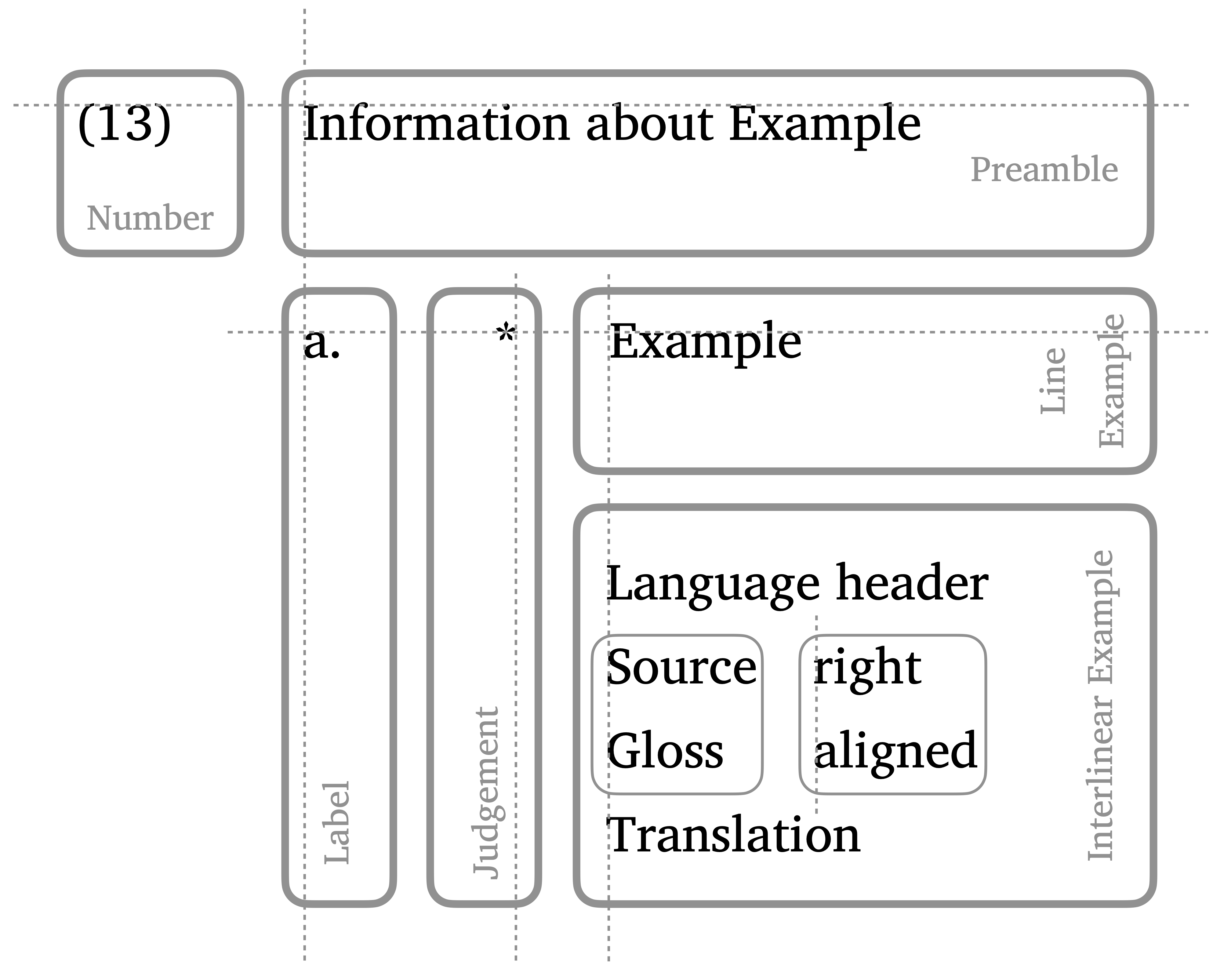

Basically, a linguistic example consists of 6 possible building blocks, of which only the number and at least one example line are necessary. The space between the building blocks is kept as minimal as possible without becoming cramped. When (optional) building blocks are not included, then the other blocks shift left and up (only exception: a preamble without labels is not shifted left completely, but left-aligned with the example, not with the judgement).

There are of course much more possibilities to extend the structure of a linguistic examples, like third or fourth subdivisions of labels (often using small roman numerals as a third level) or multiple glossing lines in the interlinear example. Also, the content of the header is sometimes found right-aligned to the right of the interlinear example (language into to the top, reference to the bottom). All such options are currently not supported by pandoc-ling.

Under the hood, this structure is prepared by pandoc-ling as a table. Tables are reasonably well transcoded to different document formats. Specific layout considerations mostly have to be set manually. Alignment of the text should work in most exports. Some CSS styling is proposed by pandoc-ling, but can of course be overruled. For latex (and beamer) special output is prepared using various available latex packages (see options, below).

pandoc-lingTo include a linguistic example in Markdown pandoc-ling uses the div structure, which is indicated in Pandoc-Markdown by typing three colons at the start and three colons at the end. To indicate the class of this div the letters ‘ex’ (for ‘example’) should be added after the top colons (with or without space in between). This ‘ex’-class is the signal for pandoc-ling to start processing such a div. The numbering of these examples will be inserted by pandoc-ling.

Empty lines can be added inside the div for visual pleasure, as they mostly do not have an influence on the output. Exception: do not use empty lines between unlabelled line examples. Multiple lines of text can be used (without empty lines in between), but they will simply be interpreted as one sequential paragraph.

::: ex

This is the most basic structure of a linguistic example.

:::| (4.1) | This is the most basic structure of a linguistic example. |

Alternatively, the class can be put in curled brackets (and then a leading full stop is necessary before ex). Inside these brackets more attributes can be added (separated by space), for example an id, using a hash, or any attribute=value pairs that should apply to this example. Currently there is only one real attribute implemented (formatGloss), but in principle it is possible to add more attributes that can be used to fine-tune the typesetting of the example (see below for a description of such local options).

::: {#id .ex formatGloss=false}

This is a multi-line example.

But that does not mean anything for the result

All these lines are simply treated as one paragraph.

They will become one example with one number.

:::| (4.2) | This is a multi-line example. But that does not mean anything for the result All these lines are simply treated as one paragraph. They will become one example with one number. |

A preamble can be added by inserting an empty line between preamble and example. The same considerations about multiple text-lines apply.

:::ex

Preamble

This is an example with a preamble.

:::| (4.3) | Preamble |

| This is an example with a preamble. |

Sub-examples with labels are entered by starting each sub-example with a small latin letter and a full stop. Empty lines between labels are allowed. Subsequent lines without labels are treated as one paragraph. Empty lines not followed by a label with a full stop will result in errors.

:::ex

a. This is the first example.

b. This is the second.

a. The actual letters are not important, `pandoc-ling` will put them in order.

e. Empty lines are allowed between labelled lines

Subsequent lines are again treated as one sequential paragraph.

:::| (4.4) | a. | This is the first example. |

| b. | This is the second. | |

| c. | The actual letters are not important, pandoc-ling will put them in order. |

|

| d. | Empty lines are allowed between labelled lines Subsequent lines are again treated as one sequential paragraph. |

A labelled list can be combined with a preamble.

:::ex

Any nice description here

a. one example sentence.

b. two

c. three

:::| (4.5) | Any nice description here | |

| a. | one example sentence. | |

| b. | two | |

| c. | three | |

Grammaticality judgements should be added before an example, and after an optional label, separated from both by spaces (though four spaces in a row should be avoided, that could lead to layout errors). To indicate that any sequence of symbols is a judgements, prepend the judgement with a caret ^. Alignment will be figured out by pandoc-ling.

:::ex

Throwing in a preamble for good measure

a. ^* This traditionally signals ungrammaticality.

b. ^? Question-marks indicate questionable grammaticality.

c. ^^whynot?^ But in principle any sequence can be used (here even in superscript).

d. However, such long sequences sometimes lead to undesirable effects in the layout.

:::| (4.6) | Throwing in a preamble for good measure | ||

| a. | * | This traditionally signals ungrammaticality. | |

| b. | ? | Question-marks indicate questionable grammaticality. | |

| c. | whynot? | But in principle any sequence can be used (here even in superscript). | |

| d. | However, such long sequences sometimes lead to undesirable effects in the layout. | ||

A minor detail is the alignment of a single example with a preamble and grammaticality judgements. In this case it looks better for the preamble to be left aligned with the example and not with the judgement.

:::ex

Here is a special case with a preamble

^^???^ With a singly questionably example.

Note the alignment! Especially with this very long example

that should go over various lines in the output.

:::| (4.7) | Here is a special case with a preamble | |

| ??? | With a singly questionably example. Note the alignment! Especially with this very long example that should go over various lines in the output. |

For the lazy writers among us, it is also possible to use a simple bullet list instead of a labelled list. Note that the listed elements will still be formatted as a labelled list.

:::ex

- This is a lazy example.

- ^# It should return letters at the start just as before.

- ^% Also testing some unusual judgements.

:::| (4.8) | a. | This is a lazy example. | |

| b. | # | It should return letters at the start just as before. | |

| c. | % | Also testing some unusual judgements. |

Just for testing: a single example with a judgement (which resulted in an error in earlier versions).

::: ex

^* This traditionally signals ungrammaticality.

:::| (4.9) | * | This traditionally signals ungrammaticality. |

For interlinear examples with aligned source and gloss, the structure of a lineblock is used, starting the lines with a vertical line |. There should always be four vertical lines (for header, source, gloss and translation, respectively), although the content after the first vertical line can be empty. The source and gloss lines are separated at spaces, and all parts are right-aligned. If you want to have a space that is not separated, you will have to ‘protect’ the space, either by putting a backslash before the space, or by inserting a non-breaking space instead of a normal space (either type or insert an actual non-breaking space, i.e. unicode character U+00A0).

:::ex

| Dutch (Germanic)

| Deze zin is in het nederlands.

| DEM sentence AUX in DET dutch.

| This sentence is dutch.

:::| (4.10) | Dutch (Germanic) | |||||

| Deze | zin | is | in | het | nederlands. | |

| DEM | sentence | AUX | in | DET | dutch. | |

| This sentence is dutch. | ||||||

An attempt is made to format interlinear examples when the option formatGloss=true is added. This will:

~ between spaces in the gloss is treated as a shortcut for an empty gloss (internally, the sequence space-tilde-space is replaced by space-space-nonBreakingSpace-space-space),::: {.ex formatGloss=true}

| Dutch (Germanic)

| Is deze zin in het nederlands ?

| AUX DEM sentence in DET dutch Q

| Is this sentence dutch?

:::| (4.11) | Dutch (Germanic) | ||||||

| Is | deze | zin | in | het | nederlands | ? | |

| aux | dem | sentence | in | det | dutch | q | |

| ‘Is this sentence dutch?’ | |||||||

The results of such formatting will not always work, but it seems to be quite robust in my testing. The next example brings everything together:

::: {.ex formatGloss=true samePage=false}

Completely superfluous preamble, but it works ...

a.

| Dutch (Germanic) Note the grammaticality judgement!

| ^^:–)^ Deze zin is (dit\ is test) nederlands.

| DEM sentence AUX ~ dutch.

| This sentence is dutch.

b.

|

| Deze tweede zin heeft geen header.

| DEM second sentence have.3SG.PRES no header.

| This second sentence does not have a header.

a. Mixing single line examples with interlinear examples.

a. This is of course highly unusal.

Just for this example, let's add some extra material in this example.

:::| (4.12) | Completely superfluous preamble, but it works … | ||||||

| a. | Dutch (Germanic) Note the grammaticality judgement! | ||||||

| :–) | Deze | zin | is | (dit is test) | nederlands. | ||

| dem | sentence | aux | dutch. | ||||

| ‘This sentence is dutch.’ | |||||||

| b. | Deze | tweede | zin | heeft | geen | header. | ||

| dem | second | sentence | have.3sg.pres | no | header. | |||

| ‘This second sentence does not have a header.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Mixing single line examples with interlinear examples. | ||

| d. | This is of course highly unusal. Just for this example, let’s add some extra material in this example. |

Also, as a quick workaround for showing multiple source lines without alignment with the glossing (e.g. for phonetic or orthographic representations of the example), it is possible to use the header of interlinear example. For a line break in the header, use the double backslash \\, either inline or at the end of a line. When you type a header using multiple lines (as shown below), then subsequent lines have to start with space. For now, this only works in the header line.

::: ex

| Example with an multiline header \\

*can be used for orthographic representations*, \\

or phonetic transcription, \\ or for whatever you like

| Dit is een lui voorbeeld=je

| DEM COP DET lazy example=DIM

| This is a lazy example.

:::| (4.13) | Example with an multiline header can be used for orthographic representations, or phonetic transcription, or for whatever you like |

||||

| Dit | is | een | lui | voorbeeld=je | |

| DEM | COP | DET | lazy | example=DIM | |

| This is a lazy example. | |||||

The examples are automatically numbered by pandoc-ling. Cross-references to examples inside a document can be made by using the [@ID] format (used by Pandoc for citations). When an example has an explicit identifier (like #test in the next example), then a reference can be made to this example with [@test], leading to (4.14) when formatted (note that the formatting does not work on the github website. Please check the ‘docs’ subdirectory).

::: {#test .ex}

This is a test

:::| (4.14) | This is a test |

Inspired by the linguex-approach, you can also use the keywords next or last to refer to the next or the last example, e.g. [@last] will be formatted as (4.14). By doubling the first letters to nnext or llast reference to the next/last-but-one can be made. Actually, the number of starting letters can be repeated at will in pandoc-ling, so something like [@llllllllast] will also work. It will be formatted as (4.7) after the processing of pandoc-ling. Needless to say that in such a situation an explicit identifier would be a better choice.

Referring to sub-examples can be done by manually adding a suffix into the cross reference, simply separated from the identifier by a space. For example, [@lllast c] will refer to the third sub-example of the last-but-two example. Formatted this will look like this: (4.13 c), smile! However, note that the “c” has to be manually determined. It is simply a literal suffix that will be copied into the cross-reference. Something like [@last hA1l0] will work also, leading to (4.14 hA1l0) when formatted (which is of course nonsensical).

For exports that include attributes (like html), the examples have an explicit id of the form exNUMBER in which NUMBER is the actual number as given in the formatted output. This means that it is possible to refer to an example on any web-page by using the hash-mechanism to refer to a part of the web-page. For example #ex4.7 at can be used to refer to the seventh example in the html-output of this readme (try this link). The id in this example has a chapter number ‘4’ because in the html conversion I have set the option addChapterNumber to true. (Note: when numbers restart the count in each chapter with the option restartAtChapter, then the id is of the form exCHAPTER.NUMBER. This is necessary to resolve clashing ids, as the same number might then be used in different chapters.)

I propose to use these ids also to refer to examples in citations when writing scholarly papers, e.g. (Cysouw 2021: #ex7), independent of whether the links actually resolve. In principle, such citations could easily be resolved when online publications are properly prepared. The same proposal could also work for other parts of research papers, for example using tags like #sec, #fig, #tab, #eq (see the Pandoc filter crossref-adapt). To refer to paragraphs (which should replace page numbers in a future of adaptive design), I propose to use no tag, but directly add the number to the hash (see the Pandoc filter count-para for a practical mechanism to add such numbering).

pandoc-lingThe following global options are available with pandoc-ling. These can be added to the Pandoc metadata. An example of such metadata can be found at the bottom of this readme in the form of a YAML-block. Pandoc allows for various methods to provide metadata (see the link above).

formatGloss (boolean, default false): should all interlinear examples be consistently formatted? If you use this option, you can simply use capital letters for abbreviations in the gloss, and they will be changed to small caps. The source line is set to italics, and the translations is put into single quotes.samePage (boolean, default true, only for Latex): should examples be kept together on the same page? Can also be overriden for individual examples by adding {.ex samePage=false} at the start of an example (cf. below on local options).xrefSuffixSep (string, defaults to no-break-space): When cross references have a suffix, how should the separator be formatted? The defaults ‘no-break-space’ is a safe options. I personally like a ‘narrow no-break space’ better (Unicode U+202F), but this symbol does not work with all fonts, and might thus lead to errors. For Latex typesetting, all space-like symbols are converted to a Latex thin space \,.restartAtChapter (boolean, default false): should the counting restart for each chapter?

true this setting will restart the counting at the highest heading level, which for various output formats can be set by the Pandoc option top-level-division.exCHAPTER.NUMBER to resolve any clashes when the same number appears in different chapter.top-level-division: chapter might be necessary in your metadata.addChapterNumber (boolean, default false): should the chapter (= highest heading level) number be added to the number of the example? When setting this to true any setting of restartAtChapter will be ignored. In most Latex situations this only works in combination with a documentclass: book.latexPackage (one of: linguex, gb4e, langsci-gb4e, expex, default linguex): Various options for converting examples to Latex packages that typeset linguistic examples. None of the conversions works perfectly, though in should work in most normal situations (think 90%-plus). It might be necessary to first convert to Latex, correct the output, and then typeset separately with a latex compiler like xelatex. Using the direct option insider Pandoc might also work in many situations. Export to beamer seems to work reasonably well with the gb4e package. All others have artefacts or errors.Local options are options that can be set for each individual example. The formatGloss option can be used to have an individual example be formatted differently from the global setting. For example, when the global setting is formatGloss: true in the metadata, then adding formatGloss=false in the curly brackets of a specific example will block the formatting. This is especially useful when the automatic formatting does not give the desired result.

If you want to add something else (not a linguistic example) in a numbered example, then there is the local option noFormat=true. An attempt will be made to try and do a reasonable layout. Multiple paragraphs will simply we taken as is, and the number will be put in front. In HTML the number will be centred. It is usable for an incidental mathematical formula.

::: {.ex noFormat=true}

$$\sum_{i=1}^{n}{i}=\frac{n^2-n}{2}$$

:::| (4.15) |

pandoc-ling#5789). In some situation this interferes with the setting of the cross-references.citeproc) should be performed after the processing by pandoc-ling. Another Pandoc filter, pandoc-crossref, for numbering figures and other captions, also uses the same system. There seems to be no conflict between pandoc-ling and pandoc-crossref.docx there is a problem because there are paragraphs inserted after tables, which adds space in lists with multiple interlinear examples (except when they have exactly the same number of columns). This is by design. The official solution is to set font-size to 1 for this paragraph inside MS Word.pandoc-ling to work properly. These are only introduced in new table format with Pandoc 2.10 (so older Pandoc version are not supported). Also note that these structures are not yet exported to all formats, e.g. it will not be displayed correctly in docx. However, this is currently an area of active developmentlangsci-gb4e is only available as part of the langsci package. You have to make it available to Pandoc, e.g. by adding it into the same directory as the pandoc-ling.lua filter. I have added a recent version of langsci-gb4e here for convenience, but this one might be outdated at some time in the future.beamer output seems to work best with latexPackage: gb4e.Originally, I decided to write this filter as a two-pronged conversion, making a markdown version myself, but using a mapping to one of the many latex libraries for linguistics examples as a quick fix. I assumed that such a mapping would be the easy part. However, it turned out that the mapping to latex was much more difficult that I anticipated. Basically, it turned out that the ‘common denominator’ that I was aiming for was not necessarily the ‘common denominator’ provided by the latex packages. I worked on mapping to various packages (linguex, gb4e, langsci-gb4e and expex) with growing dismay. This approach resulted in a first version. However, after this version was (more or less) finished, I realised that it would be better to first define the ‘common denominator’ more clearly (as done here), and then implement this purely in Pandoc. From that basis I have then made attempts to map them to the various latex packages.

The basic structure of the examples are transformed into Pandoc tables. Tables are reasonably safe for converting in other formats. Care has been taken to add classes to all elements of the tables (e.g. the preamble has the class linguistic-example-preamble). When exported formats are aware of these classes, they can be used to fine-tune the formatting. I have used a few such fine-tunings into the html output of this filter by adding a few CSS-style statements. The naming of the classes is quite transparent, using the form linguistic-example-STRUCTURE.

The whole table is encapsulated in a div with class ex and an id of the form exNUMBER. This means that an example can be directly referred to in web-links by using the hash-mechanism. For example, adding #ex3 to the end of a link will immediately jump to this example in a browser.

The current implementation is completely independent from the Pandoc numbered examples implementation and both can work side by side, like (2):

These are native Pandoc numbered examples

They are independent of pandoc-ling but use the same output formatting in many default exports, like latex.

However, in practice various output-formats of Pandoc (e.g. latex) also use numbers in round brackets for these, so in practice it might be confusing to combine both.